Politics & Current Events

You

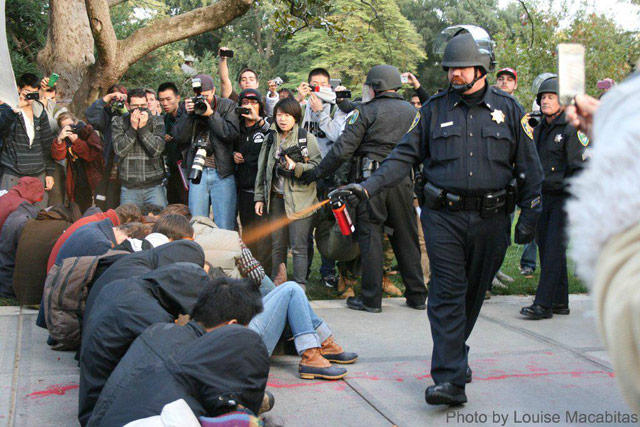

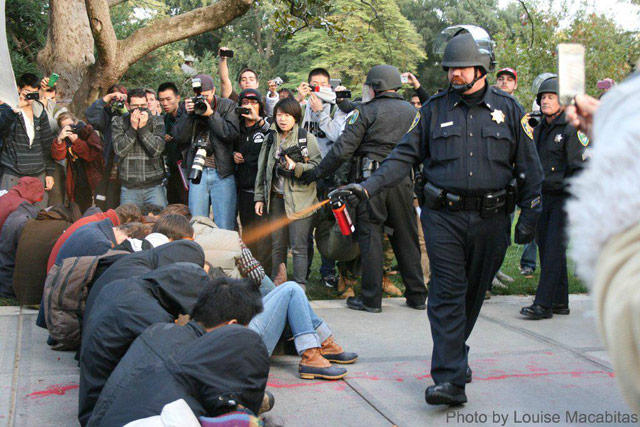

know how every time somebody in law enforcement does something that

looks bad, we're told that we should "wait until the facts are in"

before passing judgment? Well, after Lieutenant Pike of the UC Davis

Police Department became an internet meme

by using high-pressure pepper-spray on peaceful resisters, the campus

hired an independent consulting firm to interview everybody they could

find, review all the videos and other evidence, review the relevant

policies and laws, and issue a final fact-finding report to the

university. The university just released that report, along with their summary (PDF link), and the final report is even worse than the news accounts made it seem.

You

know how every time somebody in law enforcement does something that

looks bad, we're told that we should "wait until the facts are in"

before passing judgment? Well, after Lieutenant Pike of the UC Davis

Police Department became an internet meme

by using high-pressure pepper-spray on peaceful resisters, the campus

hired an independent consulting firm to interview everybody they could

find, review all the videos and other evidence, review the relevant

policies and laws, and issue a final fact-finding report to the

university. The university just released that report, along with their summary (PDF link), and the final report is even worse than the news accounts made it seem.

You probably weren't aware that the protesters warned the university that they were going to be protesting two weeks in advance, were you? The campus, and campus police, had two weeks' notice to plan for this, and yes, on day one, one question they addressed was, "What if the protesters set up an Occupy encampment?" Two weeks in advance they planned, well, if they do that, then we'll send in police to remove the tents, and to arrest anybody who tries to stop them. Now, under California law, when planning an operation like this, there's a checklist they're supposed to follow when writing the operational plan, specifically to make sure that they don't forget something important. Had they done so? They would have avoided all four of the important steps they screwed up. When asked about it? Nobody involved was even aware that that checklist existed.

The most important thing that the checklist would have warned them about was do not screw up the chain of command. Let me make clear who was in the chain of command. Under normal circumstances, it runs from university Chancellor Katehi, to campus police Chief Spicuzza, to campus police Lieutenant Davis, to his officers, including one I'll call Officer Nameless. (The report refers to him by a code letter.) Once the cops arrive on the scene, there's supposed to be one and only one person in a position to give orders to the other officers on the scene, including any higher-ups who are there (if any). Officer Nameless, who wrote the plan, was put in charge of the scene by Lt. Pike. By law, the officer in charge of the scene is not supposed to get directly involved. He or she (in this case, he) is supposed to stand back where he can see the whole scene, and concentrate on giving orders, and everybody else is supposed to refrain from giving orders. Officer Nameless instead ignored his responsibilities, and waded in, and so did Lt. Pike; Chief Spicuzza sat in her car half a block away, communicating with the radio dispatcher by cell phone, and at one time or another, all three of them, Officer Nameless and Lieutenant Pike and Chief Spicuzza were yelling out contradictory orders.

But before it even came to that point, the student protesters had, with the help of Legal Services, gone over all the relevant state laws, city ordinances, campus ordinances, and campus regulations and concluded that no matter what the Chancellor thought, it was entirely legal for them to set up that camp. When the university's legal department found out that Chancellor Katehi was going to order the camp removed, they thought they made it clear to her that the students were right.

I kept having to stop and slap my forehead over that one repeated phrase in the report: (this person or that) was under the impression she had made it clear that (some order was given), but nobody else present had that impression. Anybody who is "under the impression that they made it clear" that some order was given who who didn't put it in writing and who hasn't had that order paraphrased back to them? Should be slapped. Or at the very least demoted. Unless you actually said it, you didn't "make it clear."

It turns out that it is illegal for anybody to lodge on the campus without permission, but the relevant law only applies to people trying to make it their permanent dwelling. The law prohibits non-students from camping on campus for any reason, but neither student affairs nor the one cop sent to look could find any non-students who were there overnight. A campus regulation says that students can't set up tents without permission, but that regulation is not enforceable by police, only by academic discipline. Campus legal "thought they made it clear" that the law was on the students' side, but according to multiple witnesses, what they actually said was "it is unclear that you have legal authority to order the police to do this" and Chancellor Katehi heard that as "well, they didn't say I don't have that authority, only that it's not clear."

Chancellor Katehi, on her part, "thought she made it clear" that when police ordered the students to leave, they were (a) not to wear riot gear into the camp, (b) not to carry weapons of any kind into the camp, (c) were not to use force of any kind against the students, and (d) were not to make any arrests. But all that anybody else on that conference call heard her say out loud was "I don't want another situation like they just had at Berkeley," and Chief Spicuzza interpreted that as "no swinging of clubs."

Chief Spicuzza "thought she made it clear" more than once that no riot gear was to be worn and no clubs or pepper sprayers were to be carried. What Lieutenant Pike said back to her, each time, was, "Well, I hear you say that you don't want us to, but we're going to." And they did, including that now-infamous Mk-9 military-grade riot-control pepper sprayer that he used. Oh, funny thing about that particular model of pepper-sprayer? It's illegal for California cops to possess or use. It turns out that the relevant law only permits the use of up to Mk-4 pepper sprayers. The consultants were unable to find out who authorized the purchase and carrying, but every cop they asked said, "So what? It's just like the Mk-4 except that it has a higher capacity." Uh, no. It's also much, much higher pressure, and specifically designed not to be sprayed directly at any one person, only at crowds, and only from at least six feet away. The manufacturer says so. The person in charge of training California police in pepper spray says that as far as he knows, no California cop has ever received training, from his office or from the manufacturer, in how to safely use a Mk-9 sprayer, presumably because it's illegal. But Officer Nameless, when he wrote the action plan for these arrests, included all pepper-spray equipment in the equipment list, both the paint-ball rifle pepper balls and the Mk-9 riot-control sprayers.

The students set up their tents on a Thursday night. Chancellor Katehi ordered the cops to (a) only involve campus police, because she didn't trust the local cops not to be excessively brutal, and (b) get them out of here by 3 AM Thursday night. Chief Spicuzza had to tell her that that wasn't physically possible, they couldn't get enough backup officers from other UC campuses on that short notice, it was going to have to be Friday night at 3 AM. Chancellor Katehi said "no can do," that they had to be out of there before sunset Friday night, so that the camp wasn't joined by drunken and stoned Friday night partiers that would endanger the camp and even further endanger cops trying to deal with them -- arguably an entirely reasonable objection. So she ordered Chief Spicuzza to get them out of there by 3 PM Friday afternoon. Chief Spicuzza "was under the impression" (oh, look, there's that phrase again) that she made it clear to the Chancellor that for one thing, it couldn't be safely done, at 3:00 PM the protesters and passers-by would way outnumber her officers, and for another, it couldn't be legally done, because there was no way to legally arrest someone for "overnight camping" in the middle of the afternoon. Nobody else who was in that meeting thinks she made that clear, only that she made it clear that she didn't want to do it but couldn't explain why not. Still, when she gave the order to Lieutenant Pike, he very definitely did raise the same objections, clearly and unambiguously, backed up by multiple witnesses, who all agree that Chief Spicuzza told him, "This was decided above my level, do it anyway."

So, there's Lieutenant Pike. (Who, by the way, for obvious legal reasons since he's still being investigated by internal affairs and, last I heard, still being sued by his victims, refused to be interviewed by the consultants, so everything we know about his side of this comes from what he told other people and what he wrote in his reports.) As far as he's concerned, he's been given an illegal and impossible order: take 40 or so officers - unarmed and unarmored officers - into an angry crowd of 300 to 400 people who aren't doing anything illegal and make that crowd go away without using any force or getting any of your officers injured. For reasons Stanley Milgram could explain, it does not occur to Lieutenant Pike to disobey this order, so instead, he does the best he can, using his own judgement to decide which parts of his orders and which parts of the law to ignore. Unsurprisingly, it goes badly. Backed into a corner by an angry crowd (which has, by the way, demonstrably left him room to retreat, even with his prisoners, contrary to what he says in his report) that is confronting him with evidence that he is the law-breaker here, not them, he snaps. And rather than take it out on the more-powerful people who put him in this situation, he takes it out on the powerless and peaceful people in front of him, using a high-pressure hose to pump five gallons of capsacin spray into the eyes and mouths of the dozen or twenty people in front of him ... and he would have used more if he'd had it, he only stopped when he did, halfway through his third pass down the line, because the sprayer emptied. When he gets back to the station, Chief Spicuzza (who has no idea what's just happened) congratulates him in front of half the department for how well he just did. And now, as far as he's concerned, he's being hung out to dry. We're apparently supposed to ignore the fact that multiple video sources contradict almost everything about his after-incident report because apparently, in his opinion, he was only following orders.

This is not better than the initial media reports. This is worse. This is an epic textbook in official-violence failure.

Dear Community,

Our tech team has launched updates to The Nest today. As a result of these updates, members of the Nest Community will need to change their password in order to continue participating in the community. In addition, The Nest community member's avatars will be replaced with generic default avatars. If you wish to revert to your original avatar, you will need to re-upload it via The Nest.

If you have questions about this, please email help@theknot.com.

Thank you.

Note: This only affects The Nest's community members and will not affect members on The Bump or The Knot.

Our tech team has launched updates to The Nest today. As a result of these updates, members of the Nest Community will need to change their password in order to continue participating in the community. In addition, The Nest community member's avatars will be replaced with generic default avatars. If you wish to revert to your original avatar, you will need to re-upload it via The Nest.

If you have questions about this, please email help@theknot.com.

Thank you.

Note: This only affects The Nest's community members and will not affect members on The Bump or The Knot.

Sometimes, When "All the Facts are In," It's Worse: The UC-Davis Pepper-Spray Report

Dunno if this was posted yet.

http://bradhicks.livejournal.com/459368.html

Sometimes, When "All the Facts are In," It's Worse: The UC-Davis Pepper-Spray Report

- Apr. 15th, 2012 at 8:24 PM

You

know how every time somebody in law enforcement does something that

looks bad, we're told that we should "wait until the facts are in"

before passing judgment? Well, after Lieutenant Pike of the UC Davis

Police Department became an internet meme

by using high-pressure pepper-spray on peaceful resisters, the campus

hired an independent consulting firm to interview everybody they could

find, review all the videos and other evidence, review the relevant

policies and laws, and issue a final fact-finding report to the

university. The university just released that report, along with their summary (PDF link), and the final report is even worse than the news accounts made it seem.

You

know how every time somebody in law enforcement does something that

looks bad, we're told that we should "wait until the facts are in"

before passing judgment? Well, after Lieutenant Pike of the UC Davis

Police Department became an internet meme

by using high-pressure pepper-spray on peaceful resisters, the campus

hired an independent consulting firm to interview everybody they could

find, review all the videos and other evidence, review the relevant

policies and laws, and issue a final fact-finding report to the

university. The university just released that report, along with their summary (PDF link), and the final report is even worse than the news accounts made it seem.You probably weren't aware that the protesters warned the university that they were going to be protesting two weeks in advance, were you? The campus, and campus police, had two weeks' notice to plan for this, and yes, on day one, one question they addressed was, "What if the protesters set up an Occupy encampment?" Two weeks in advance they planned, well, if they do that, then we'll send in police to remove the tents, and to arrest anybody who tries to stop them. Now, under California law, when planning an operation like this, there's a checklist they're supposed to follow when writing the operational plan, specifically to make sure that they don't forget something important. Had they done so? They would have avoided all four of the important steps they screwed up. When asked about it? Nobody involved was even aware that that checklist existed.

The most important thing that the checklist would have warned them about was do not screw up the chain of command. Let me make clear who was in the chain of command. Under normal circumstances, it runs from university Chancellor Katehi, to campus police Chief Spicuzza, to campus police Lieutenant Davis, to his officers, including one I'll call Officer Nameless. (The report refers to him by a code letter.) Once the cops arrive on the scene, there's supposed to be one and only one person in a position to give orders to the other officers on the scene, including any higher-ups who are there (if any). Officer Nameless, who wrote the plan, was put in charge of the scene by Lt. Pike. By law, the officer in charge of the scene is not supposed to get directly involved. He or she (in this case, he) is supposed to stand back where he can see the whole scene, and concentrate on giving orders, and everybody else is supposed to refrain from giving orders. Officer Nameless instead ignored his responsibilities, and waded in, and so did Lt. Pike; Chief Spicuzza sat in her car half a block away, communicating with the radio dispatcher by cell phone, and at one time or another, all three of them, Officer Nameless and Lieutenant Pike and Chief Spicuzza were yelling out contradictory orders.

But before it even came to that point, the student protesters had, with the help of Legal Services, gone over all the relevant state laws, city ordinances, campus ordinances, and campus regulations and concluded that no matter what the Chancellor thought, it was entirely legal for them to set up that camp. When the university's legal department found out that Chancellor Katehi was going to order the camp removed, they thought they made it clear to her that the students were right.

I kept having to stop and slap my forehead over that one repeated phrase in the report: (this person or that) was under the impression she had made it clear that (some order was given), but nobody else present had that impression. Anybody who is "under the impression that they made it clear" that some order was given who who didn't put it in writing and who hasn't had that order paraphrased back to them? Should be slapped. Or at the very least demoted. Unless you actually said it, you didn't "make it clear."

It turns out that it is illegal for anybody to lodge on the campus without permission, but the relevant law only applies to people trying to make it their permanent dwelling. The law prohibits non-students from camping on campus for any reason, but neither student affairs nor the one cop sent to look could find any non-students who were there overnight. A campus regulation says that students can't set up tents without permission, but that regulation is not enforceable by police, only by academic discipline. Campus legal "thought they made it clear" that the law was on the students' side, but according to multiple witnesses, what they actually said was "it is unclear that you have legal authority to order the police to do this" and Chancellor Katehi heard that as "well, they didn't say I don't have that authority, only that it's not clear."

Chancellor Katehi, on her part, "thought she made it clear" that when police ordered the students to leave, they were (a) not to wear riot gear into the camp, (b) not to carry weapons of any kind into the camp, (c) were not to use force of any kind against the students, and (d) were not to make any arrests. But all that anybody else on that conference call heard her say out loud was "I don't want another situation like they just had at Berkeley," and Chief Spicuzza interpreted that as "no swinging of clubs."

Chief Spicuzza "thought she made it clear" more than once that no riot gear was to be worn and no clubs or pepper sprayers were to be carried. What Lieutenant Pike said back to her, each time, was, "Well, I hear you say that you don't want us to, but we're going to." And they did, including that now-infamous Mk-9 military-grade riot-control pepper sprayer that he used. Oh, funny thing about that particular model of pepper-sprayer? It's illegal for California cops to possess or use. It turns out that the relevant law only permits the use of up to Mk-4 pepper sprayers. The consultants were unable to find out who authorized the purchase and carrying, but every cop they asked said, "So what? It's just like the Mk-4 except that it has a higher capacity." Uh, no. It's also much, much higher pressure, and specifically designed not to be sprayed directly at any one person, only at crowds, and only from at least six feet away. The manufacturer says so. The person in charge of training California police in pepper spray says that as far as he knows, no California cop has ever received training, from his office or from the manufacturer, in how to safely use a Mk-9 sprayer, presumably because it's illegal. But Officer Nameless, when he wrote the action plan for these arrests, included all pepper-spray equipment in the equipment list, both the paint-ball rifle pepper balls and the Mk-9 riot-control sprayers.

The students set up their tents on a Thursday night. Chancellor Katehi ordered the cops to (a) only involve campus police, because she didn't trust the local cops not to be excessively brutal, and (b) get them out of here by 3 AM Thursday night. Chief Spicuzza had to tell her that that wasn't physically possible, they couldn't get enough backup officers from other UC campuses on that short notice, it was going to have to be Friday night at 3 AM. Chancellor Katehi said "no can do," that they had to be out of there before sunset Friday night, so that the camp wasn't joined by drunken and stoned Friday night partiers that would endanger the camp and even further endanger cops trying to deal with them -- arguably an entirely reasonable objection. So she ordered Chief Spicuzza to get them out of there by 3 PM Friday afternoon. Chief Spicuzza "was under the impression" (oh, look, there's that phrase again) that she made it clear to the Chancellor that for one thing, it couldn't be safely done, at 3:00 PM the protesters and passers-by would way outnumber her officers, and for another, it couldn't be legally done, because there was no way to legally arrest someone for "overnight camping" in the middle of the afternoon. Nobody else who was in that meeting thinks she made that clear, only that she made it clear that she didn't want to do it but couldn't explain why not. Still, when she gave the order to Lieutenant Pike, he very definitely did raise the same objections, clearly and unambiguously, backed up by multiple witnesses, who all agree that Chief Spicuzza told him, "This was decided above my level, do it anyway."

So, there's Lieutenant Pike. (Who, by the way, for obvious legal reasons since he's still being investigated by internal affairs and, last I heard, still being sued by his victims, refused to be interviewed by the consultants, so everything we know about his side of this comes from what he told other people and what he wrote in his reports.) As far as he's concerned, he's been given an illegal and impossible order: take 40 or so officers - unarmed and unarmored officers - into an angry crowd of 300 to 400 people who aren't doing anything illegal and make that crowd go away without using any force or getting any of your officers injured. For reasons Stanley Milgram could explain, it does not occur to Lieutenant Pike to disobey this order, so instead, he does the best he can, using his own judgement to decide which parts of his orders and which parts of the law to ignore. Unsurprisingly, it goes badly. Backed into a corner by an angry crowd (which has, by the way, demonstrably left him room to retreat, even with his prisoners, contrary to what he says in his report) that is confronting him with evidence that he is the law-breaker here, not them, he snaps. And rather than take it out on the more-powerful people who put him in this situation, he takes it out on the powerless and peaceful people in front of him, using a high-pressure hose to pump five gallons of capsacin spray into the eyes and mouths of the dozen or twenty people in front of him ... and he would have used more if he'd had it, he only stopped when he did, halfway through his third pass down the line, because the sprayer emptied. When he gets back to the station, Chief Spicuzza (who has no idea what's just happened) congratulates him in front of half the department for how well he just did. And now, as far as he's concerned, he's being hung out to dry. We're apparently supposed to ignore the fact that multiple video sources contradict almost everything about his after-incident report because apparently, in his opinion, he was only following orders.

This is not better than the initial media reports. This is worse. This is an epic textbook in official-violence failure.

Re: Sometimes, When "All the Facts are In," It's Worse: The UC-Davis Pepper-Spray Report